There were some evident challenges when I saw the floor plan. Instinctive choices that I would make as a gallery attendant — like where to start my visit or what pathway to follow inside — suddenly became stories I planned as the curator. Maybe I could use the columns as a portal entry to create separate spaces in each exhibition and Yes! That difference in the ceiling height will definitely make that corner the most intimate place for reflection. The question remained as to what to do with that 21-foot wall. The Millstone Gallery at the Center of Creative Arts (COCA) has two entries. While one of them has a welcoming reception, facing directly toward the wall that traditionally displays the vinyl signs describing the exhibition, the other opens to a hall that lengthens the distance between the spectators and the pieces. I asked the artistic team if I could revitalize that area, envisioning that forgotten wall as an interactive space that will encourage people to perform often restricted actions inside a gallery: to touch, to be loud, to destroy, to reclaim.

From the Guerrilla Girls to movements like StrikeMoma, a plethora of activists and scholars have discussed the access barriers surrounding art institutions. Besides the lack of representation of minoritized identities and the economic disparities that continue to make art education a class privilege, museum and gallery norms police bodies in public spaces. In my experience leading tours in WashU’s Kemper, the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, and COCA, it is common for visitors to need a couple of minutes to relax their bodies, as they immediately assume that a museum is a place where touching, moving and congregating are highly discouraged. While most publics accept these limitations as part of the necessary efforts for conserving pieces, art institutions should be aware of the emotional toll that their surveilling of the body has on the experience of witnessing art. Adding an interactive wall to COCA’s Millstone was not only an opportunity to reflect on the power dynamics assumed as normal in creative spaces, but also an invitation to feel back the art in the body, to interpret the art more viscerally and holistically.

My first interactive wall — designed for the show Everything Is Golden by artist Lizzy Martinez — challenged the prohibition of touching materials and the predominance of sight in art exhibitions. By mounting ecologies of natural and synthetic, of slick and rough/uneven materials in shadow boxes, I prompted visitors to question how notions of care and worth feel to the skin. How would your perceptions of a concrete sculpture change after being able to feel cold concrete clumps and their dust lingering on your fingers?

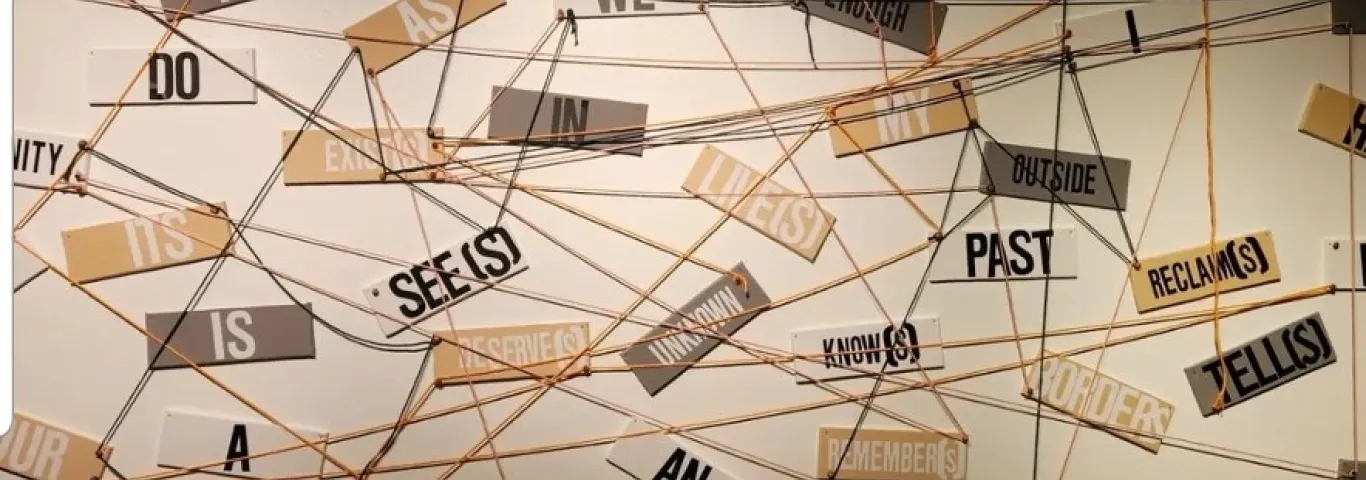

My most recent interactive provides a space for storytelling in Mga Kuwento Namin (Stories We Tell). This exhibition displays portraits of Filipino-American women in today’s St. Louis overlayed by three projections of the Philippine villages at the 1904 World Fair. Artist Ria Unson explains how racialized and colonial stereotypes keep being projected onto the Filipino community in the present and that, in order to interrupt such images, visitors need to walk in front of the projectors and cast shadows over the portraits. The portraits’ titles are statements shared by every woman and reproduced in their native dialect in a looped audio: Na sa aking likhang-isip ang tunay kong tahanan (Tagalog); Brilla (Chabacano). After long conversations with Ria, we decided to not have an immediate translation of the phrases in the labels, to encourage people to make an effort to get to know the language and disrupt assumptions that minoritized communities and their cultures should always be available and transparent for their consumption. I used the idea of “taking time to know each other’s stories” and designed a wall where weaving a story would necessarily require crossing and touching other threads: There is not “I reclaim my past” without “we exist outside borders.” The more visitors tell their stories, the more visible the shared routes are — the wall becomes a growing testimony of collaboration and conviviality.

As I write these reflections, I received the photographs of the opening. I noticed with joy how many of the pictures in front of the interactive wall are of groups hugging. Is it because while crafting the stories they were having fun? Is it because there is just enough space in the hallway? I wonder why I am this surprised of watching people hugging in the gallery. Shouldn’t hugging be a common occurrence inside the galleries?

Headline photo by Karla Aguilar Velásquez